Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon), Vietnam

I got ready this morning to see the sites of Ho Chi Minh City. I first walked to Independence Palace (or “Reunification Palace”). After a bomb attack on the old Independence Palace (so named in 1954) on February 27, 1962, the president of the Saigon Republic (or South Vietnam, depending on what history you read), Ngô Đình Diệm, commissioned the Vietnamese architect Ngô Viết Thụ to design the current structure, which took four years to complete; Ngô Đình Diệm was assassinated in 1963 and his successor, Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, assumed the presidency in October 1967 and occupied the palace; then, on April 21, 1975, Nguyễn Văn Thiệu abdicated his presidency and on April 30, 1975, the North Vietnamese entered the palace grounds and raised their flag, thus achieving “the liberation of the South”. The palace has five levels and a bunker with conference rooms, reception rooms, offices, a library, a bedroom and war room for the president inside the bunker, a communications room and a command center inside the bunker, apartments, a cinema, a game room, a shooting range, a dance floor with bar (located in a room on top of the roof), and a helicopter landing pad; there are also three tennis courts on the palace grounds, a pavilion, a conference center, and now two tanks (identical to the ones that stormed the palace on April 30, 1975) and a F5E fighter aircraft (identical to the one flown by Lieutenant Nguyen Thanh Trung on April 8, 1975 when he dropped two bombs on the palace after infiltrating the Southern Republic’s Air Force) – surprisingly there wasn’t a swimming pool to take a break from the heat of the day. I walked around the palace looking inside each of the rooms (set up as they would’ve looked back in 1975) and really admired the 1960s-looking furniture (simple, but stylish); I also enjoyed looking at the wartime maps in the bunker and the old communications equipment on display. After exploring every level of the palace, I then exited the grounds and walked westward to my next stop.

I soon reached the War Remnants Museum, which opened on September 04, 1975 and is dedicated to researching, collecting, preserving, and exhibiting the remnant proofs of war crimes committed by France, the United States, and the Southern Republic (i.e. South Vietnam) during the Vietnam conflict (1950 – 1975); the museum’s stated intention is “to call the public to say no to war – yes to peace”, but I believe this goal would be better achieved if they showcased the war crimes committed by all sides during the war (let us be honest: in war, all parties are guilty of crimes, it’s part of our human nature and crimes are more likely to happen during wartime when many of the dregs of society become soldiers); certainly the United States committed many horrendous crimes during the Vietnam War and I felt the museum did an okay job in portraying this (mostly through photographs); although the most truthful information I found in the museum was on blown up pictures of Life magazine articles that told a more complete story – the authors of these articles also did not feel any need to add negative adjectives to describe the United States or South Vietnam (or North Vietnam for that matter) as many displays in the museum did (these articles were also definitely not pro-war). Overall, the museum was incredibly one-sided and by omitting the whole truth, I felt the stated intention rings false. Anyway (now that I got my thoughts out on that subject), upon entering the museum grounds, I was surprised to see so many aircraft, tanks, artillery, bombs, and other weapons from the United States on display in a foreign country; I then entered in to the building and looked around at the displays of American aggression, pictures taken by war photographers, artifacts from around the world opposing the war in Vietnam, and – most heart-wrenching of all – photographs displaying the effects of Agent Orange on human beings, generation after generation (there were also stillborn fetuses caused by Agent Orange on display as well) – it’s despicable that the United States used chemicals in warfare and it is absolutely saddening that so many people are still suffering from the consequences (these photographs make me want to completely eliminate chemicals unnatural to our environment from ever being used again; after all, dioxin isn’t the only chemical capable of deforming humans, pesticide ingredients can also terribly affect our health and cause children to be born with deformities). Unfortunately, the museums in this city apparently all close for lunch time; so, at 11:55, all visitors were kicked out (but able to return later today on the same ticket).

I then walked to Notre Dame Cathedral, but that too was closed (until 15:00!); then I visited the old Post Office building and looked inside there before walking north to the Museum of History. Along the way, I stopped for a foot long sub at Subway (salami, pepperoni, cheese, and marinara sauce) during a rain shower (which came suddenly and ended just as suddenly, as I entered the plaza with the Subway restaurant). After that lunch, I continued north and came to the museum shortly after 13:10; I then waited for it to open back up at 13:30. The museum covered the history of the Vietnamese people from Prehistoric times (up to 2879 BC), to the Bronze Age (2879 BC – 179 BC), to the period of Chinese occupation (179 BC – 938 AD), to the early dynasties (939 – 1407), and to the later dynasties (1428 – 1945); it also had exhibits on Champa culture (2nd – 17th centuries), Oc Eo culture (1st – 7th centuries), current minority cultures, Buddhist statues and ceramics collected from around Asia, cannons used in Vietnam (from the 17th-19th centuries), and a mummified body of a woman that died and was buried in the late 19th century in Saigon – there was also a water puppetry theater, but no show was on at the time (it is actually a puppet show on/in a pool of water). The museum displayed many miniature dioramas depicting victories over foreign aggressors and maps showing where insurrections occurred against occupiers over the last two millennia – Vietnam has a long history of occupation and attacks by many nations (the Chinese, Khmer Empire, France, United States). Some of the best artifacts on display were intricately designed ceramics produced in Vietnam during the dynastic period; unfortunately I obeyed the “no photographs” signs despite other tourists and a security guard (with his cellphone!) taking photos of many exhibitions. I learned a lot about Vietnamese history, so I thought the museum was definitely worth a visit, although it was small and it only took an hour to go through all the exhibits.

After visiting the museum, I then walked to the Jade Emperor Pagoda; along the way, I crossed one of the most dangerous roads for a pedestrian to cross; there was a never ending onslaught of motorbikes and cars on the road (most of the intersections and roads in this city appear to have a ceaseless stream of traffic and during my twenty-four hours here I’ve noticed a few tourists recording the constant flow of motorbikes in amazement – it’s a modern wonder), so I had to do like the locals and just cross, hoping all the vehicles would slow down or go around me; actually, out of all the cities I’ve been to, Ho Chi Minh City is the worst city to walk around in, which is somewhat odd since sidewalks are plentiful and usually large (despite all the motorbikes, cars, food vendors, and shopping stalls that take up most of the sidewalks – like in pretty much every Asian country – there is still a good bit of room to navigate), but motorbikes treat these sidewalks as secondary roads and will travel both ways on them (despite many policemen in green uniforms standing all over the city, they will travel right past them, so I guess it isn’t illegal (?)) – this is similar to most Asian countries, but here they will travel at greater speeds and in greater numbers -; also many people will travel down the wrong side of the road on their motorbikes – once again, this is like most Asian countries, but they seem to do it more frequently here (making walking against traffic dangerous since you constantly have to watch behind you); lastly, as mentioned above, there is a constant flow of traffic and in great quantities. Honestly, after a few more days here, I’ll end up with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and never be able to cross a street again. I finally (and safely) reached the Jade Emperor Pagoda, which is a Taoist pagoda built by the Chinese community in 1909. I walked inside and looked around at the many figures on display and admired the detailed wood carvings found throughout the pagoda; I also liked seeing some very old mechanical fans and an old safe used to collect donations (it was like walking in to a time warp). As I was inside the pagoda, rain began to pour down, so the staff there closed the openings in the roof (for ventilation and sunlight) and I stayed inside longer than I normally would have (at least I enjoyed the smell of incense). Eventually the rain died down, and I walked out of the Pagoda.

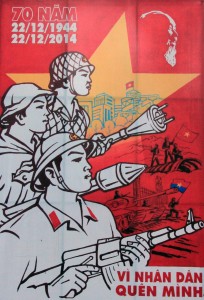

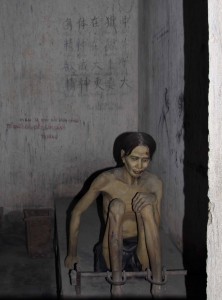

I returned to the War Remnants Museum and looked at the exhibits I missed before the lunch break. I read the history on display detailing the chronology of events from declaration of independence from France in 1945 to the fall of Saigon in 1975. I then walked out to the exhibit on the brutal prisons and methods of torture used by the South Vietnamese, which was a far cry from humane (once again, completely one-sided; anyone who knows the history, knows that the North Vietnamese were equally guilty in this category – Hanoi Hilton anyone?). Then I walked around the outside of the museum again to take one last look at the aircraft, before heading south. I tried to find a statue of Uncle Ho (the affectionate name given to Ho Chi Minh by the Vietnamese people) that was supposed to be near the Ho Chi Minh City Hall (a historic building with a beautiful facade, but one that does not permit photographs (what could they possibly have to hide?), so I cannot display it here), but due to on-going construction in front of the city hall (they’re building a metro rail), the statue has been moved (I do not know where). I then walked to the Saigon Opera House – a beautiful building – to inquire about tickets to a show, but was told to come back tomorrow because the box office was closed. I then walked back toward the hostel, stopping at a Saigon Tourist shop to buy an overpriced tour ticket to the Cu Chi tunnels (don’t buy anything from this company, the hostel I’m staying at is selling the same tour for a third of the price), and then I stopped at another Trung Nguyên Coffee shop where I had a small cup of french-pressed (it was a cute, little, metallic press) coffee with condensed milk (the milk was a mistake since it overpowered the taste of the coffee) and their signature ice cream concoction (which was delicious). I then finally made it back to the hostel and began typing away at today’s journal entry (these entries have been getting longer, and longer, and longer, and longer as of late – I may need to scale them back in size); I also had a bottle of Pocari Sweat and a Sports Water to replenish my liquids and provide me with much needed electrolytes (the Sports Water, produced in Singapore, tasted like a liquid version of the candy Smarties). Eventually I went to sleep to get a good night’s rest before setting out to explore more of the city tomorrow.