Sonargaon, Bangladesh

I slept in a little today, exhausted from a long day of traveling yesterday. When I did wake up, I took my time getting ready and eventually made it out of the hotel. Once out in the sun, I walked south to the Gulistan Bus Stop, which is located on the road next to Bangabandhu National Stadium (the stadium is named after the “Father of Bangladesh”); the road’s eastern edge was lined with buses (that looked like they were well past their “use by” date) and on the sidewalk were several tables set up, each with a man seated behind it selling bus tickets; I stopped at the first two tables I came across and was directed each time to walk further down to reach the table selling tickets to Mograpara (the city and bus stop closest to Sonargaon); I finally found the correct table, bought my ticket (43 taka), and was then directed on to the bus. The bus ride from Dhaka to Mograpara lasted about an hour and it seemed that most of the route had garbage lining the side of the road, just dumped there as if it was the world’s longest trash dump (this is certainly a bit of an exaggeration, but there really was a lot of trash piled on the side of the road and there were even some poor souls scavenging through the waste). The bus finally reached Mograpara and I exited the bus, walking through the chaotic streets that were filled with people and rickshaws (both the bicycle and motorized variety). A man peddling a rickshaw came up to me and asked if I wanted a ride to Panam Nagar (a street lined with derelict mansions built around the turn of the last century by Hindu cloth merchants); he gave me a price of fifty taka to take me to the street, but I asked him if he would show me around Sonargaon instead, to see the different sites; we ended up agreeing on a price of two hundred taka and we were then on our way, traveling north through Sonargaon (which means “City of Gold”). Sonargaon is located in the center of the Ganges Delta (a delta that dominates most of Bangladesh) and used to be the capital of the ancient kingdom ruled by Isa Khan of Bengal. My peddler drove the rickshaw to Panam Nagar, passing by an old bridge from the Mughal times, still standing and still in use; once we reached the street, I got out of the rickshaw to walk along the aged avenue (the peddler wanted to whisk me through the street on the rickshaw, but this site demanded I take my time with the camera and capture as much of it as possible); I walked up and down the street, looking at the decaying facades, peeking over the brick walls placed in the mansions’ doorways to keep the untidy messes out, and I even went in to a small derelict structure, walked up the stairs, and had a rooftop view of the street. There was also a group of young people who stopped taking photos of themselves to take photos with me – this happens a lot to Caucasians in Bangladesh on account of them not getting many foreign tourists (. . . which is completely understandable; after all, if someone is going to spend the money to travel to Asia, why go to Bangladesh when every other country in South, Southeast, and East Asia has much more to offer and is easier to get around?).

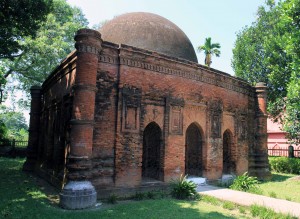

After satisfying my photographic desire, I climbed back aboard the rickshaw and my peddler took me next to Goaldi Mosque, which is a pre-Mughal mosque built in 1519 AD by Mulla Hizabar Akbar Khan; it is a small square brick building with a dome on top. After stopping and walking around that old mosque, I checked out a nearby mosque still in use, and then climbed back aboard the rickshaw. There was a man on a bicycle trying to get me to employ him as a guide, but I turned him down and instead asked to be taken to the Folk Art and Craft Museum next to Bara Sardar Bari (a very nice old mansion that – unfortunately for my visit – is in the process of being extensively restored).

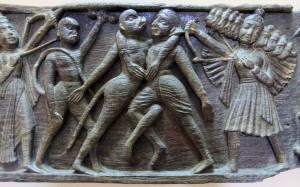

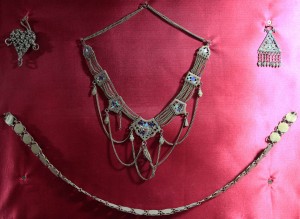

During the ride over to Bara Sardar Bari, the rickshaw peddler demanded I pay him 1000 taka as opposed to the agreed upon 200 taka; I told him I would go as high as 300 taka (this was what I was going to give him anyway – 100 taka more as a tip); he persisted on demanding “1000” and I told him “300”. We reached the entrance to the park surrounding the museum and I bought the ticket to go inside; I then overheard the rickshaw peddler talking to other peddlers and mentioning the 1000 taka; so I turned around and shook my index finger at him, told him “no”, and proceeded to walk inside the park; he followed, was stopped by security, I explained the situation, and I ended up paying 200 taka for his services and walked away since that was what we agreed upon (it was still an overpayment based upon what I read on the internet and even his own price of 50 taka to take me to the museum); the security guard who acted as mediator looked as though he had seen this before and was completely on my side (probably because he’s intelligent enough to know not to sour the precious few tourists this country sees, otherwise there will be less next year); once again, I realized it is better just to walk everywhere as long as I am capable and to deprive all taxi/tuk-tuk/rickshaw drivers of my money, especially since they are all pretty much gutter trash criminals. That bullshit aside, I walked through the park which had many festive activities going on, no doubt since it was still Eid-ul-Azha; there were children on manually-operated rides, booths with games and food, boats out on the lake, and many families just hanging around and having a picnic. I walked to the Folk Art and Craft Museum and hung around outside to finish a water bottle I had just bought; while I was outside drinking the water, Bangladeshi after Bangladeshi came up to me to take photos with me (I was like a C-list celebrity and probably could’ve gotten into any Mussul[wo]man’s panties that tickled my fancy . . . or my dick). After taking many photos with random people, I finally walked inside the museum and looked around at all the artifacts on display; it was a very nice collection and worth a visit. I then walked out to the old mansion next to the museum, Bara Sardar Bari; I took photos around the mansion and more Bangladeshis took photos with me. I then exited the museum and park grounds, walking south toward Mograpara.

I reached the main highway that cuts through Mograpara after about a half hour of walking; I then crossed the highway and walked along the side of the creek before turning northward to the town; I came across a historic building with a bunch of kids playing football in the dirt patch next to it; they stopped to practice their English greetings on me (e.g. “hi”, “hello”, “how are you?”) and then they all posed for me to photograph them (they just viewed the picture through the screen on the back of the Canon; that’s all they wanted); I then left and continued walking through the winding streets in this small village, passing by several mosques, a field used in silk production, and poor dwellings; I then reached the Tomb of Sultan Ghiyassuddin Azam Shah, who was the third Sultan (from 1390-1411 AD) of the first Iliyas Shahi dynasty of Bengal. I then left the tomb and wandered back through the streets of Mograpara before reaching the creek again, which I then followed back to the built up shopping area near the highway. Once I reached the highway, I found the correct bus to take back to Dhaka’s Gulistan Bus Stop, paid for my ticket, and climbed aboard.

It took roughly an hour to get back to Gulistan Bus Stop from Mograpara. I disembarked the bus at a very busy intersection and I walked north through crowds of many sellers and buyers, stepping around all the goods being hawked on the ground. I then reached the hotel, rode the elevator up to my floor, dropped my camera and tripod off, relaxed a short while, and then went upstairs to the restaurant on the nineteenth floor to have dinner; I ended up eating the chicken biryani dish, a bowl of fried mixed vegetables, a large bottle of water, and a cup of tea. I then went back to my room and rested until I fell asleep; then I rested some more.