Kanchanaburi, Thailand

. . . and in to the next day. Since the train was late departing, it was certainly late arriving. I kept looking out the window and finally (at 04:20), we arrived at Nakhon Pathom; I had made it through the toughest hours, between 01:00 and 04:00 (in the past, regardless of how much sleep I had gotten the night before or when I had woken up the morning/afternoon before, I have always had trouble keeping my eyes open during those hours). I disembarked the train, checked at the ticket counter when the train to Kanchanaburi was scheduled to depart (09:00), and then walked to the nearby 7-11 for liquids and energy (in the form of a cold can of espresso). I then mostly sat around the station thinking – since my iPhone battery was nearly dead, I could not risk reading anymore -, but did some walking around in the vicinity next to the station. After night turned to day, I walked across the Charoensattha Bridge to Phra Pathom Chedi Temple (means “first holy stupa”). The bridge itself was built by the royal command of H.M. King Rama VI to allow the public to easily walk between the railway station and the temple; the temple is the tallest stupa in Thailand (two meters shorter than the tallest in the world – Jetavanaramaya, which stands at 122 meters in Sri Lanka) and is quite impressive to behold – unfortunately the sky was covered in clouds, otherwise the golden-brown stupa would’ve shined in sunlight. Also, as people were waking up in the city, businesses were opening up and many food stalls were frying and grilling away to provide breakfast to those in need of it. When the clock reached 08:00, I bought my onward train ticket to Kanchanaburi (I was told I could not purchase it earlier) while watching the Thai national anthem be broadcast on the television set behind the ticket counter. I then waited some more . . . until the train finally arrived shortly after 09:00 (nearly on time – not bad).

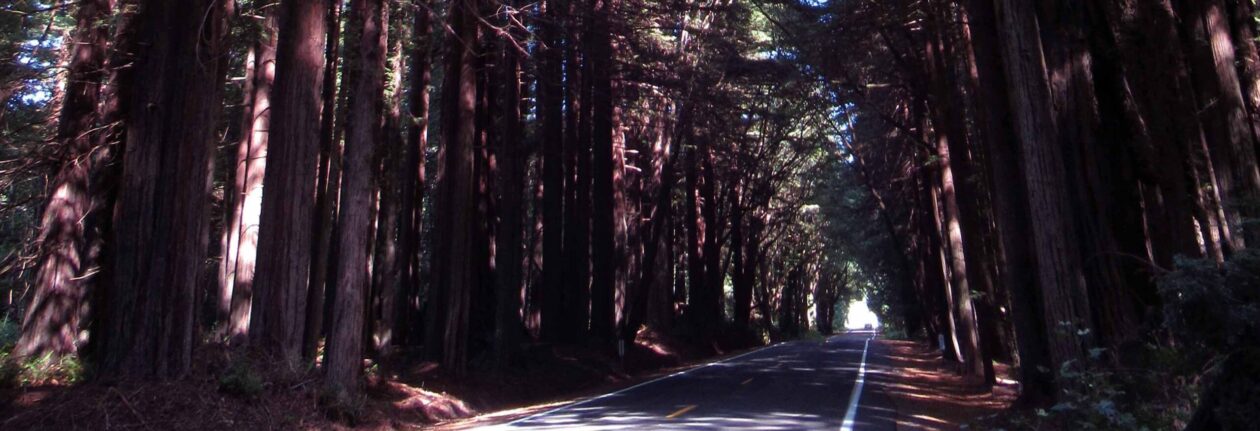

I boarded the train and ended up sitting next to a German man who was studying Civil Engineering at his university; before discovering his major, I had told him that the job I had just quit was a civil engineering job, so this had put me an interesting spot when he began to ask me questions about my past profession, but I was able to supply adequate answers and luckily he didn’t ask any technical questions. During the train ride north, I noticed the brush was very close to the train in some places (almost like a wall of vegetation) and the speeding train did clip some of the leaves off, landing them inside the car; we also passed through Nong Pladuk Railway Station – the starting station for the Thai-Burma Railway built by the Japanese and finished on September 16, 1942. After traveling for about an hour and a half, the train reached Kanchanaburi; I got off and then walked in to the city; first I passed by the War Cemetery, which is the final resting place for numerous Allied men from Australia, Great Britain, the Netherlands, Americans, and local men who perished during World War II; then I passed by the adjacent Thai cemetery which had many tombs in small mounds built up to house the remains. I continued walking through the city, heading west to the Kwae Yai River; from the river, I walked south through many packs of dogs (some less friendly than others) to a guesthouse that got great reviews online; luckily the guesthouse had vacancies and I was able to check in; the owner of the guesthouse inquired what my plans were and I told him I would like to see Hellfire Pass; he gave me all the details on how to get there and get back and then took me on a motorbike to the bus station and directed me to which bus I needed to take.

After waiting about twenty minutes at the bus station, the bus departed and we were heading north. During the bus ride I nodded off for about twenty minutes, but once I woke up again adrenaline kicked in as I realized I was nearing my destination. After a nearly two hour ride, I was dropped off by the road leading to Hellfire Pass (also known as “Konyu Cutting”). I walked to the museum and inside I read about the history of the Thai-Burma Railway: in 1942 the Japanese decided to build a railroad from Ban Pong, Thailand to Thanbyuzayat, Burma (415 kilometers long) to supply their forces fighting the British in Burma; over 250,000 Asian laborers (known as “Romusha”) and 60,000 Allied POWs (British, Australian, American, and Dutch) comprised the workforce to build the Thai-Burma Railway, of those, 12,399 POWs and between 70,000-90,000 Asian laborers died due to lack of food, inadequate medical care, and brutal treatment from Japanese and Korean guards and supervisors (I was not previously aware of Koreans being employed by the Japanese during the war until now and evidently they were just as brutal toward the laborers as the Japanese were). Of the entire railway route, Hellfire Pass was the most infamous portion; cut in two sections (one at 73 meters long and 25 meters deep and the other at 450 meters long and 8-10 meters deep) the POWs were forced to work long hours well in to the night; using bamboo torches during the night and laborers toiling away at the rock, the scene looked like something out of Dante’s ‘Inferno’, thus the name “Hellfire Pass”. After visiting the museum, I walked along the ground where the railway once stood (it was disused after the war and vegetation took over until the Australians decided to conserve the site and turn it in to a memorial); I walked through Hellfire Pass, then to the Kwae Noi Valley Lookout, then through “Hammer and Tap” cutting (another, albeit shorter, cutting through the mountain), to where the Three-tier Bridge once stood; at this point I turned around because it was getting late and I did not want to miss the bus back to Kanchanaburi (80 kilometers away). I hurried back along the trail where the railway once stood, past the museum, and then out to the highway where the bus stop was located. I made it back with plenty of time because it was another forty minutes before the bus came.

When the bus did come, I boarded the bus, paid my fare, and, in about two hours, I was back at the bus stop in Kanchanaburi. I then walked back to the guesthouse I was staying at, dropped my camera and tripod off, and then walked to a nearby restaurant along the river to eat dinner. Sitting right beside the Kwae Yai River, I had Moo Paar Pad-Ped (jungle fried pork (whatever that means) with spicy chili and peppercorn), chicken fried rice, beer, and water. After dinner, I walked back to the guesthouse, watched some television, and finally went to sleep at about 22:20 (having been awake for over thirty-nine hours – if one discounts the twenty minutes I nodded off during the bus ride to Hellfire Pass).